The history of law, obtained from legal texts as a discipline, addresses issues that range from its origin and its evolution over the centuries; and that is taught in law schools.

The first manifestations of Law occur in prehistoric times, mainly in the way in which our ancestors established legal norms in societies; ruled by kinship, or under the command of the elders of a tribe.

In the history of civilizations, rules have been established and the power of the legislator to dictate laws, sanctioning non-compliance with it.

The origin of the Law is given from a relationship of force between unequal people with the intention of regulating the intention of whoever intends to control or dominate another.

The intention of the Law is in order to compensate a physical or moral offense that one person inflicts on another; ensuring a penance to whoever transgresses the physical or moral to another individual.

The Law is a discipline whose object consists of the knowledge of the legal systems that is born to regulate the compensation for the breach of a given word or commitment.

The history of law will show us the events and their development in historical events. In this context, the sociology of law will deal with the succession of singular events in a certain historical process; as well as, on the social reality of law.

Historical origin of the Law | Law history

In prehistoric times, the social organization was of very low development, inasmuch as there was no private property or social classes, since everything was communal.

The division of labor was determined according to age and sex, delegating specific activities to children and women according to their physical condition.

Non-existence of the State and absence of Law in the primitive Community

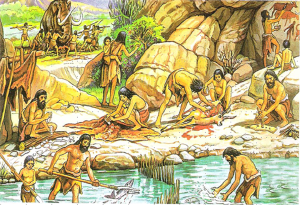

In prehistoric times, men were organized into groups dedicated to hunting, fishing, and gathering, and labor was based on cooperation.

According to Karl Marx, this type of collective or cooperative production was the result of the helplessness in which the isolated individual found himself, and of the inexistence of socialization and the means of production. Consequently, primitive man did not have private ownership of the instruments of production, only those that served them to defend themselves against wild beasts.

In this economic regime, production was directly determined by collective needs, and there was no social mediation.

This way of life corresponds to the Paleolithic period, but with the discovery of agriculture and livestock, carried out during the Neolithic, the first social division of labor emerged; in which the peasant villages still conserved a good part of social egalitarianism and, later, social classes and political and religious power clearly appear.

In primitive communism there was no inequality of goods, nor the need for a State, since individuals lived in a society based on self-consumption, where all their social relations were communal.

Historical origin of the Law | Law history

In prehistoric times, the social organization was of very low development, inasmuch as there was no private property or social classes, since everything was communal.

The division of labor was determined according to age and sex, delegating specific activities to children and women according to their physical condition.

Non-existence of the State and absence of Law in the primitive Community

In prehistoric times, men were organized into groups dedicated to hunting, fishing, and gathering, and labor was based on cooperation.

According to Karl Marx, this type of collective or cooperative production was the result of the helplessness in which the isolated individual found himself, and of the inexistence of socialization and the means of production. Consequently, primitive man did not have private ownership of the instruments of production, only those that served them to defend themselves against wild beasts.

In this economic regime, production was directly determined by collective needs, and there was no social mediation.

This way of life corresponds to the Paleolithic period, but with the discovery of agriculture and livestock, carried out during the Neolithic, the first social division of labor emerged; in which the peasant villages still conserved a good part of social egalitarianism and, later, social classes and political and religious power clearly appear.

In primitive communism there was no inequality of goods, nor the need for a State, since individuals lived in a society based on self-consumption, where all their social relations were communal.

Historical origin of the Law | Law history

In prehistoric times, the social organization was of very low development, inasmuch as there was no private property or social classes, since everything was communal.

The division of labor was determined according to age and sex, delegating specific activities to children and women according to their physical condition.

Non-existence of the State and absence of Law in the primitive Community

In prehistoric times, men were organized into groups dedicated to hunting, fishing, and gathering, and labor was based on cooperation.

According to Karl Marx, this type of collective or cooperative production was the result of the helplessness in which the isolated individual found himself, and of the inexistence of socialization and the means of production. Consequently, primitive man did not have private ownership of the instruments of production, only those that served them to defend themselves against wild beasts.

In this economic regime, production was directly determined by collective needs, and there was no social mediation.

This way of life corresponds to the Paleolithic period, but with the discovery of agriculture and livestock, carried out during the Neolithic, the first social division of labor emerged; in which the peasant villages still conserved a good part of social egalitarianism and, later, social classes and political and religious power clearly appear.

In primitive communism there was no inequality of goods, nor the need for a State, since individuals lived in a society based on self-consumption, where all their social relations were communal.

Organization of the primitive community

The economic structure of the primitive community consisted of a society where there was collective ownership of the means of production. Therefore, production was carried out jointly, which resulted in the community distribution of goods.

In the absence of private ownership of the means of production, social classes did not exist either and, therefore, the social relations of production of the primitive community were based on mutual cooperation. It was a self-consumption and self-subsistence society.

The production instruments came from the stone in its natural state that was then carved and polished. Later, metals were used (copper, bronze and iron) and, finally, axes, bows, knives and other instruments began to be made.

In addition, the natural division of labor is created, determined by sex and age, delegating certain activities aimed at women and children.

The woman was in charge of the distribution of the production, which gives it an economic and also political importance; which leads us to matriarchy as a fundamental and decisive characteristic in the affairs of society.

Likewise, the first social division of labor was established, separating individuals who engaged in hunting and fishing, and those who worked in agriculture and herding; which allowed an increase in production and productivity.

As the development of society continues, the economic surplus is created, making exchange possible and merchants emerge.

Collective ownership of the means of production evolved in such a way that collective ownership became familiar and, later, private property.

Social norms and social power

Social norms are a large group of rules that are adjusted to the behaviors, tasks and activities of the human being. The word moral comes from the Latin moralis, translated into Greek éfhos. However, the Latin translation loses its initial meaning, as it later refers to character or custom.

Now, morality is defined as a set of norms or rules that regulates the actions of individuals among themselves.

Society dictates the rules that individuals must abide by to live in it and are the defense of the social structure, giving rise to morality.

In every human relationship there are groups that can be represented by the head of a family, the teacher of a school, the head of labor, union leader, etc.

Power is subject or conditioned by the highest hierarchy, which can be represented by the government of a nation. This is what is known as political power, representative of all the wills of a society and therefore sovereign, that is, it is not subject to any other power.

Likewise, power can be understood as a collective will, which rests on the individual capacity to inspire, govern or demand the conduct of others; thus establishing a relationship between freedom and order. In conclusion, it can be said that society is represented by social order and authority.

Extinction of the primitive community

The primitive community disappears with the evolution of the means of production, the division of labor and the organization of a society.

The Metal Age begins the end of the primitive community regime, while the Chalcolithic period is characterized by the evolution of agriculture and livestock; as well as the beginning of metallurgy, in the middle of the V millennium BC. by C.

Metalworking began in the Near East, especially Anatolia, Syria, Mesopotamia, and Iran, spreading to the Mediterranean; copper being the first forged metal. However, bronze (copper and tin alloy) was forged in the middle of the 4th millennium BC. by C.

Bronze and iron were great advances in the evolution of mankind. The use of these metals promoted commerce and navigation; as well as, in improving agricultural techniques by replacing the stone wheel with the metallic one, and the same happened with the plow.

The military organization had armies provided with bronze weapons, which allowed them to dominate the peoples who had Neolithic and Chalcolithic culture. Subsequently, armies carrying iron weapons subdued those who still fought with bronze weapons. Wars left many prisoners who were later turned into slaves.

The transformation and improvement of the tools, allowed a greater development of agriculture and livestock and the production of surpluses that led to the emergence of social differences.

Then, the first religious constructions made with gigantic stone blocks or megaliths were produced. These megalithic monuments are known as dolmens, menhirs, and cromlechs.

The invention of writing | Law history

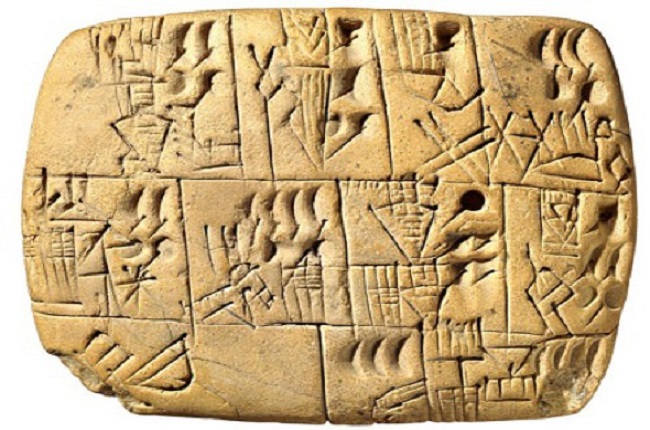

History begins with written records and the evolution of writing was a process originated by economic practice and in the ancient Near East.

Clay tokens were used to represent goods or units of time spent at work, but a high degree of complexity was reached when the need to handle numbers greater than one hundred arose. For this reason, different types of tokens were used that were wrapped with clay and with marks that differentiated them from one another. These markings soon replaced tokens and later clay writing tablets.

The earliest known writings were invented by the Egyptians who developed the hieroglyphs and the Mesopotamians who invented the cuneiform script.

The original writing system was Mesopotamian (3500 BC) and by the end of the 4th millennium BC. C., a triangular-shaped stylet was used that was pressed on flexible clay (cuneiform writing). Thus, the invention of the first writing systems coincides with the beginning of the Bronze Age in the last half of the IV millennium BC. in Sumeria.

Over time, the scriptures evolved and allowed ancient societies to write their own laws for the coexistence of their citizens. Such is the case of the Code of Hammurabi, one of the first laws written in ancient Macedonia.

The Hammurabi Code and the Talion Law (1750 BC) | Law history

The Code of Hammurabi is one of the first laws written in ancient Mesopotamia, around 1700 BC. of C. This code contains two hundred and eighty-two laws written by scribes on twelve tablets. It was inscribed with cuneiform characters on a 2.4 m high cylindrical diorite stone stela.

Above the top of the code is a relief sculpture representing King Hammurabi receiving the insignia of power, the ring and the scepter, from the god Šamaš or Marduk.

Hammurabi’s code has a specific structure and stipulates a punishment for each transgression of the law. These punishments involve the death penalty, disfigurement and the philosophy of an eye for an eye, the Law of Talion.

Its content consists of a prologue, 282 laws and an epilogue, which regulate social and economic life in all its aspects; as well as, a rigorous and implacable penal system, based on the “Talion Law”.

The Hammurabi code, being the first penal and civil code of humanity, suggests that both the accused and the accuser have the opportunity to provide evidence; being an example of the principle of presumption of innocence.

On the other hand, the death penalty was frequently applied even for minor crimes, as well as vagrancy or false testimonies, among other offenses.

The oldest piece of the Code of Hammurabi is preserved in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

The Law in Ancient Greece | Law history

The law in ancient Greece cannot be understood as a legal system, because each polis was governed by its own system of laws.

The polis, commonly defined as City-State, were groups of non-foreign citizens who, through public discussion and vote, decided on the measures to be taken in the various political and social problems.

In the 8th century BC. C., a Greek from the Boeotian region, carried out a work destined to establish justice as an elemental virtue, beginning the long tradition developed by Plato and Aristotle.

The law arose entirely from the formation of the individual as part of the polis, that is, it resulted from the formation of the individual and from his orientation towards the “right path.”

In the legislation of Lycurgus, a source of Greek idealism is presented in law, giving greater importance to the strength of education and the formation of citizen conscience than in legal prescriptions, that is, he preferred the legislative tradition of the democracy of the 4th century.

He also placed a greater emphasis on training men according to the mandatory norms of the community, moving away from individualism.

Procedural laws

In general, historians consider Athenian law to be about rights, obligations, and crimes. Athenian laws used to be written as “if someone does A, then B is the result.”

The Athenians were more concerned with the legal actions that must be carried out by the prosecutor, rather than strictly defining on which acts should be tried. This resulted in the jury having to decide whether the offense that had been committed was in fact or a violation of the law.

Development of Athenian law

The codification of the Athenian laws written by Dracon of Tesalia, probably were given between 621 and 620 a. C., which survived the reforms of Solón. Dracon’s homicide law was in force in the 4th century BC. de C. and distinguished between premeditated and involuntary homicide; it also provided the assassin’s reconciliation with the dead man’s family.

The Athenian codes of laws established by Dracon were entirely reformed by Solon, the eponymous archon from 594-593 BC. These reforms included the cancellation of the debts and directed to the property of the Earth, as well as the abolition of the slavery for those individuals born in Athens.

Judicial system and courts

The ancient Greek courts were run by laymen, whose officials charged little or nothing for their services. Most of the processes were carried out on the same day and individual cases were resolved even faster.

There were no lawyers or judges, nor were court officials magistrates. A typical case consisted of two litigants, one of whom argued that an illegal act had been committed, while the other claimed that it was not illegal, or that nothing had happened. The jury decided if the defendant was guilty, and what the punishment should be. In the courts of Athens, the jury consisted of ordinary people, while the litigants came mainly from the elites of society.

Solon (638 – 558 BC) | Law history

Solon was a native poet, political reformer and legislator of the city of Athens, considered one of the Seven Sages of Ancient Greece.

The Constitution of him of the year 594 a. C. involved numerous reforms aimed at alleviating the situation of the peasant who was besieged by poverty, the debts that sometimes led to his enslavement and a stately regime that led him to misery.

Institutional reforms and the new census system were created with the aim of abolishing the distribution of political rights based on the lineage of the individual and, instead, implemented the timocratic system.

Census system

Solon organized a timocratic system that divided the non-foreign and free population into four classes according to the volume (in medimnos or medimnoi) of their agricultural production. In this way, the political rights of each individual that were based on lineage and came to be considered according to his wealth were abolished.

The highest class was that of the pentacosiomedimnoi (Pentakosiomedimnoi), who had incomes greater than 500 medimnos. These had the fullness of their political rights, so they could elect or be elected to occupy any government position (including archon).

In times of war they held the highest military positions and their members were entrusted to deliver the so-called “liturgies.” These included the armament of a warship (trierarchy), the financing of an embassy abroad or the staging of a theatrical piece (coregía).

The second social class was that of the hippeis, with incomes of over 300 medimnos. These enjoyed the same rights as the pentacosiomedimnos and had to render their services as knights.

On the other hand, the third of the classes was constituted by the Zeugitas (Zeugitai), whose income was greater than 200 medimnos. This social group could not be elected or participate in the election of the archon, but it could occupy the other positions. They had to join the hoplites (heavy infantry militia) and bear the costs of their weapons.

The last class was made up of the tetes (thetes), with incomes of less than 200 medimnos. These could not be elected for any position; but if they could participate in the election of those positions other than the archonist. This group, in times of war, constituted the light infantry and they were the majority of the rowers of the fleet of Athens.

Legislation and Social Reforms

Solón implemented reforms in the legislation aimed at alleviating the situation of the peasant who was besieged by poverty and debts that often led to his enslavement; and even submit to a stately regime that led to misery.

Agricultural reforms

Solón annulled the debts contracted by the peasants so that they could recover their seized lands. This legislation was called sixachteia or “removal of charges.”

Abolition of debt slavery

In his legislation, Solon repealed the current law in which it was possible to collect debts by enslaving the debtor and his relatives (hektemoroi).

Once this law came into force, the archon bought slaves in order to free them and prohibited the enslavement of the debtor and the Athenian.

Economic policy

In economic matters, some laws prohibited the export of cereals outside the Attica region, however, they promoted the export of olive oil and handicrafts.

A law was also drafted that required the father to teach a trade to his children; however, they were exempted from the obligation to maintain it during old age, if they had not received such education.

Among the measures that he imposed to avoid leisure in economic terms, Solón maintained Dracon’s law, and replaced the punishment of capital punishment with fines and deprivation of civil rights (atimia).

On the other hand, if a foreigner settled with his family in Athens and started an industry or trade, he could apply for the right of citizenship.

Solon’s legislation prohibited costly funerals and the immolation of animals in honor of the deceased. Likewise, he also forbade the erection of tombs that cost more than ten people could build in the course of three days.

Athens changed its unit of measurement, coming from Fidón, by one of its own; and he made a new Athenian coin lighter than the Aegina, which was the one in progress at the time.

Solón also modified the current legislation regarding the right of inheritance. He established the right of male individuals who did not have children, to bequeath their property to any other person, whether related or not. Before the reform, the assets passed to the estate of the deceased’s family or his brotherhood.

Marriage

Plutarco attributes to Solón the first Athenian laws regarding the care of the paternal patrimony after the marriage. Said legislation established that if a man married to an heiress without male siblings could not bear children, she had the right to leave him and marry a close relative; Thus the inheritance that the wife received from her father was maintained in the family lineage. The husband of an epíclera, was forced to have sexual relations with her at least three times a month.

In addition, the delivery of dowry by the wife was eliminated, in order to reduce unions for economic purposes. The bride, at the time of marriage, only had to wear three dresses and jewelery of little value.

Sexuality

According to some authors, Solon gave a formal framework to Athenian sexual customs, alluding to the establishment of public brothels in Athens. This has been an attempt to “democratize” sexual pleasure and, in turn, to promote the idea of a citizen “owner of his pleasures.” However, several authors question the veracity of this fact.

The regulation of the practice of pedophilia was an important aspect in this legislation. Solón drew up certain norms destined to regulate this practice and to protect free young people; since it was frequent that they exercised naked in the gyms and were seduced by mature spectators. A norm also prohibited the access of the male slaves to these enclosures and any attempt of loving relation between slaves and free young people.

Other reforms

Solon’s reforms limited the absolute ancestral dominion of a father over his family; the prohibition of a man from selling his wife or children as slaves or their expulsion from the home; and the benefit of maintenance at the expense of his offspring was limited to food, clothing, and burial.

Old Age: The State and the Right in the slavery | Law history

Roman Law is formed by a set of principles of law that governed Roman society until the death of Emperor Justinian.

The Roman State

Ancient Rome designates the State that emerged from the expansion of the Roman Empire that spanned from Great Britain to the Sahara desert and from the Iberian Peninsula to the Euphrates. After its foundation, according to

n the tradition in 753 BC. C., Rome was an Etruscan monarchy, which later, in the year 509 a. C. it happened to be a Latin republic and, finally, in 27 a. C. became an empire.

The city of Rome arose from the settlements of Latin, Sabine and Etruscan tribes, being a city-state ruled by a king (rex) chosen by a council of elders (senatus).

The Roman Republic was established in 509 BC. C., when the king was exiled, according to the last writings of Tito Livio, and a system of consuls was implemented. Consuls, initially made up of patricians and later commoners, were elected officials who exercised executive authority that grew in size and power with the establishment of the Republic. In this period, institutions such as the Senate, the magistracies and the army were established.

The expansion of the Empire caused profound changes in Roman society. The inadequate political organization caused that all the attempts of change were blocked by the conservative senatorial elite. In the 1st century BC. C. produces an institutional crisis that led to various revolts, revolutions and civil wars.

César Augusto, after being the victor in the civil wars, abolished the republic to consolidate a one-person and centralized government of the entire territory; establishing the Roman Empire.

The so-called Roma Quadrata foundation on the Palatine Hill is attributed to three tribes: the Ramnes, the Ticians and the Luceres.

Roman Law

Roman law was the legal order that governed the citizens of Rome; since its foundation in 753 BC. de C.) until the compilation of the Corpus Juris Civilis; made by Emperor Justinian I, in the middle of the 6th century AD.

Roman law remains in the following periods:

- The monarchy, from the founding of Rome in the middle of the 8th century BC until the expulsion of King Tarquinio the Proud in 509 BC. of C ..

- The Roman Republic, from 509 BC At this time the Law of the XII Tables was published, in the years 451 and 450 a. of C. that constitute the base of republican Roman law; the State rests on the powers of the magistrates; and after the political crisis in the 1st century BC. C., the Senate grants the absolute power of the Roman State to Octavio Augusto, in the year 27 a. by C.

- The Principality, from the year 27 a. Until the middle of the second century. Period in which the State was authoritarian, under the regime of the Emperor or Prince.

- The Dominated or absolute Empire, from the middle of the second century to 476 AD. of C., year in which the Roman Empire of the West disappears. At this time, the Emperor has absolute power and dictates the so-called “imperial constitutions”; the Empire of the ancient Roman religion is converted to Christianity by the Edict of Thessalonica, in 380 AD. C .; Germanic invasions lead to the decline and disappearance of the Western Empire.

- Finally, the government of Justinian I (527-565) in the Eastern Empire, a time when the Corpus Juris Civilis was compiled, in 549 AD. C .; composed of the Code, the Digest or Pandectas.

The law of Rome

The first Roman citizens are called patricians (or patres), who had the full right of citizenship, being those of the highest social class.

Their rights were: suffrage, the performance of political or religious public office, allocation of public lands, guardianship, succession, power, marrying other members of the gens, the patronage, contracting and making a will. This set of rights constituted the ius qüiritium or ius Ciudavitatis.

As obligations, the patricians had the duty to render military service, and to contribute with certain taxes to the maintenance of the State.

The court

The jurisdiction is concentrated in the city, where the King has his “court” in which he orders the so-called “curul chair” assisted by the bailiffs, and in front of the litigating parties.

Some crimes had special judges such as the duoviri perduellionis for the insurrection; the quaestores paricidii for murder or the three viri nocturni; some special officers for cases related to fires, security agent and vigilance of executions.

Torture could only be applied to slaves and pre-trial detention was the general rule.

On the other hand, capital punishment was applicable to whoever disturbed the public peace, and for other crimes. This was applied in several ways: False and traitorous witnesses were thrown; the the Harvest drones were hung and arsonists were burned alive.

But there was also the right of appeal (provocatio), where the people had the power to grant pardons.

As for the fines, they were paid with the delivery of oxen or sheep, or they were beaten.

Civil trials were judged by the king or by a commissioner appointed by the monarch.

In case of theft the thief could pay a satisfactory repair; otherwise he would become a slave to the aggrieved.

If injuries were committed, compensation was arranged, and if there were injuries, the injured party could claim the Talion (cause the same damage).

The State exercised the guardianship of minors and the incapable. Slaves could be manumitted or freed. The liberation could be private if the master decided to retract and recover the slave, or public if the liberation was perpetual and irrevocable.

Slavery

After the disintegration of the primitive community society, the productive forces generated new conditions that gave rise to a new social organization, slavery.

The Egyptian, Babylonian and Phoenician cultures developed through slavery as a mode of production and private ownership of the means of production was developed.

There were two antagonistic and fundamental social classes in all ancient societies: the slave owners who are the owners and the slaves who are the means of production.

The base of production is represented by the slave who performs productive activities.

Some tests of the slave mode of production are:

- The development of agriculture in Egypt, where new crops such as wheat, oats and millet were established.

- The construction of the pyramids and the Egyptian tombs.

- Livestock farming develops and the curation of skins used for clothing grows.

- The use of precious stones (rubies and diamonds) for the production of drills and other instruments used for cutting and drilling.

- Irrigation systems covered the collection, conduction and distribution of water for agriculture and livestock.

Trade developed widely in slavery, appearing merchants dedicated to the purchase and sale of slaves. Likewise, the currency appeared as a means of exchange for products. Slave social relations of production were exploitative and were based on private ownership of the means of production, the product and the producer.

The monarchy as a political organization

The Roman monarchy (in Latin, Regnum Romanum) was the first political form of government in Rome, since its foundation on April 21, 753 BC. of C., until 509 a. of C .; when the last king Tarquin the Proud, was expelled and the Roman republic was established.

The newly founded city-state is ruled by a king chosen by a council of elders. In the monarchy, the king is elected for life and is conferred supreme authority.

At the same time, the King was head of the army, high priest and Judicial Magistrate, both for civil and criminal matters. On the death of the monarch, power is exercised by an Inter rex of the senate, until the election of a new monarch.

The senate was composed, at first by the patres or seniors, that is, the heads of patrician families who were older, who formed a council to advise the King.

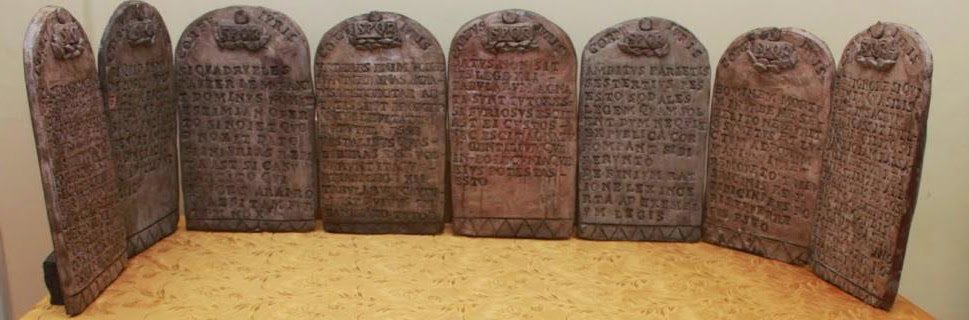

The XII Tables (451 BC) | Law history

The Law of the XII Tables was a legal text that established the norms directed to the coexistence of the Roman people. The XII Tables constitute the basis of the republican Roman law of ancient Rome.

Its elaboration took place around the middle of the 5th century BC, when the Republican Senate sent a commission of three magistrates to Athens to know the legislation of the Greek ruler Solon; which was inspired by the principle of equality before the law.

The Senate decided to constitute another commission made up of ten patriotic magistrates and chaired by a consul for the elaboration of the Law; drawing up the first ten tables in 451 BC.

In 450 BC Another commission is created, this time made up of patricians and commoners, to prepare tables eleven and twelve.

The XII Tables were ratified by the Senate and approved by the popular assemblies in the celebration of the centurian elections.

Content of the Law of the XII Tables

The contents of the XII Tables were arranged as follows:

Tables I, II and III: Rules relating to private procedural law:

The procedure that regulates the legal actions that Roman citizens could exercise for the defense of their rights. The process was characterized by its excessive formalism, where the parties had to pronounce certain words, obligatorily if they wanted to have a chance of winning the litigation or had to perform rites.

The praetor was the magistrate who presided over the process, and the judge who passed sentence was a citizen chosen by the parties.

The execution of the conviction of a debtor constituted a principle of legal certainty, where he received the punishment from him in case of being insolvent.

Tables IV and V: Rules on Family Law and Succession

They regulate norms regarding the guardianship of minors not subject to parental authority after the death of the father; or to the conservatorship, to administer the assets of those disabled people. There would also be rules to protect single women, leaving them in charge of their closest relatives, upon the death of their father.

In these tables the absolute power of the father (paterfamilias) over his family is legally limited. In this norm the divorce was established in favor of the woman, allowing her to be absent for three days from the marital home. And in the case of the children, the paterfamilias lost their homeland potes tad if he exploited them commercially three times. Consequently, the son was emancipated.

In matters of inheritance, if this was intestate, the law established the heirs in their own right as the first heirs. This involved the children and the wife. If there were no heirs, then the closest relative (agnate) to the deceased who were in the power of a common ancestor inherited. If there were no agnate heirs either, people who derived from the same gens as the deceased inherited.

Tables VI and VII: Rules on the Law of Obligations and Real Rights

These rules regulated the legal business of the nexum, in which the debtor was obliged to make the benefit to the creditor. In the event of non-compliance, he would be subject to the authority of the creditor without the need for a court ruling. The nexum was repealed by the Poeteliae-Papiliae law.

They also regulate the stipulatio or sponsi, in which the debtor assumes the obligation to make the benefit to the creditor, and in the event of non-compliance, the creditor could take a legal action to obtain a judicial sentence.

In the real rights the mancipatio and the in iure cessio were established. These consisted of legal businesses that allowed the transfer of ownership of res mancipi (means of production; capital, farms, buildings, slaves, draft and pack animals, etc.).

The mancipatio consisted of conducting the legal business before a libripens, an official who carried the balance, and 5 witnesses. For its part, the in iure cessio was carried out before the praetor, who acted as the notary, and was in charge of giving public faith to the business.

The usucapio consisted of the acquisition of a property in good faith through the passage of time and with fair title (two years for real estate, one year for personal property).

In addition, the Law of the XII Tables established norms on neighborly relations between neighboring farms.

Tables VIII and IX: Rules on public law

In these Tables the distinction between Criminal Law, Public Law and Private Law appears implicitly.

Public law would deal with criminal offenses such as treason against the Roman people or homicide. The criminals were persecuted and punished with capital punishment or exile.

The private would apply to private, less serious and persecution crimes at the request of the victim or her family. These crimes were punished with a pecuniary penalty in favor of the victim, depending on the seriousness of the crime: Delicta (crimes of damage to property of third parties), furtum or theft and inuria or crime of injuries.

Table IX established the prohibition of granting privileges, promoting equality among citizens before the law.

Table X: Rules regarding burials, cremations and funerals

Table X prohibited burial or cremation within the city to preserve public health, prevent fires, or prevent excessive luxury at funerals.

Tables XI and XII: Norms regarding the prohibition of contracting mixed marriages

Tables XI, XII prohibited contracting mixed marriages, between patricians-plebeians. This norm was repealed by the Canuleia Law, a jurisprudence of the Roman Republic.

With the enactment of Laws I and II or “Tabulae iniquitous” (Tables of injustices), the concubinage or marriages between patricians and commoners were punished.

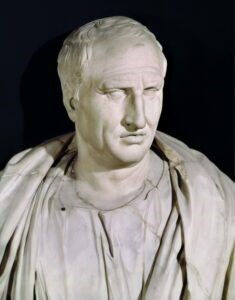

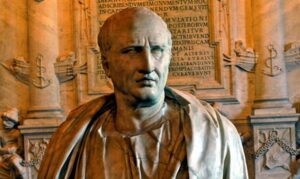

Marco Tulio Cicero (106 – 43 BC) | History of Law

Marco Tulio Cicero was a Roman jurist, politician, philosopher, writer, and orator; considered one of the greatest rhetoricians and stylists of Latin prose in the Roman Republic.

As a lawyer, Cicero was one of the most famous jurists in Rome. In Greece, he was a disciple of the Epicurean Phaedrus and the Stoic Diodotus. He continued his studies at the Academy and moved to Rhodes to meet the master of oratory, Molón de Rodas, and the stoic Posidonius.

He pursued his political career as a quaestor in Sicily in 76 BC, and in 70 BC. He agreed to defend the Sicilians oppressed by the former magistrate Verres; being very popular among the populace as a lawyer.

Universally he is recognized as one of the most important authors of Roman history. Cicero introduced the famous Hellenic schools of philosophy to the republican intelligentsia, as well as the creation of a philosophical vocabulary in Latin.

Cicero was a great orator and renowned lawyer, who focused his attention on his political career. He was also a philosopher and writer.

As a defender of the traditional republican system, Cicero fought the dictatorship of Julius Caesar. During his career, he did not hesitate to change his position depending on the political climate.

After Caesar’s death, Cicero became an enemy of Marco Antonio. He was outlawed as an enemy of the state by the Second Triumvirate and, consequently, was executed by soldiers after being captured in an attempt to flee the Italian peninsula, in 43 BC. C.

Cicero’s work

Trained in the main philosophical schools, Cicero showed an antidogmatic attitude and collected aspects of the various currents. The originality of his philosophical works is scarce, but he became a crucial element in the transmission of Greek thought. As a man of letters, he became the model for the classical Latin prose, perfectly bound together (De divinatione).

Like the famous Cato, Cicero always put his talents at the service of the Republic. He makes great contributions to the study of Rhetoric and Philosophy. He desires to offer his fellow citizens an educational model; promoting love of the country and a morality close to stoicism.

Rhetoric had become an indispensable weapon in the hands of a certain aristocracy in order to exercise power. Cicero not only stood out as an orator but also as a theorist on the subject. During his early years, he was a disciple of the most important jurists of his time such as Mucio Escévola, who instilled in him the ideas of the Scipios circle.

Cicero, lover of Greek culture, retorica and philosophy

Cicero learned to love Greek culture and the study of Philosophy. On the other hand, he developed a tireless activity in favor of his fellow citizens as a politician, lawyer and writer-philosopher in order to communicate his discoveries and intellectual achievements.

His debut in the forum with the speech pro Quinctio (81) and, after him in his pro Sexto Roscio Amerino, in which he highlighted some of the evils of Lucio Cornelio Sila’s tyranny; a late-republican dictator. For this reason, Cicero decided to leave Rome for a time and directed his steps towards Athens and Rhodes to complete his training there between the years 79 and 77. During that time, he acquired a broader philosophical and rhetorical training. In Rhodes he was next to the rhetor Molón to comply with the rules of the so-called Rhodian School.

In Greece, he continued his training with the philosopher Posidonius. In Smyrna, he met Publius Rutilio Rufo. Then, Cicero returned to Rome, where, after the death of Sulla, he to continue his political career.

Cicero’s political career

In Sicily, he was appointed quaestor (regular magistrate of lesser rank) from 75 to 76 BC. of C., position that he exercised with honesty, and in the year 66, he was appointed praetor.

In 70 a. of C., Cicerón accepted to carry out the accusation in front of the defender of the proconsul Verre, the famous Hortensio, one of the most famous orators of the moment. Cicero was victorious by delivering the five speeches that he had prepared, and with them he gained fame as a lawyer.

Cicero was appointed consul in the year 63 a. of C., after aborting the famous conspiracy of Catilina. He was hailed as the savior of the country. For this, he was punished with exile and a year later, he returned to Rome to restart his oratorical activity.

The political situation in Rome was immersed in an atmosphere of tension, which influenced his defense of Milo. Milo was accused of the murder of his former enemy Clodius; an agent of Julius Caesar, at the beginning of ’52.

Ultimately, Cicero assumed the post of governor in Cilicia (51-50 BC) and the political crisis worsened with Caesar’s decision to start a new civil war.

Cicero’s Last Conflicts

In this conflict, Cicero was inclined to support Pompey, who represented the ideals of the old Republic; but later he decided to ask for forgiveness and support Julius Caesar. To earn his confidence, Cicero wrote his three Caesarian speeches: Pro Marco Marcelo, Pro Quinto Ligario and Pro rege Deiotaro.

After the murder of Caesar, in the year 44 a. of C., Cicerón tried to recover the political power of him and attacked Marco Antonio in his 14 speeches titled Filípicas; him achieving the enmity of the Roman military man, who sentenced him to death.

Cicero died in 43 BC. of C. at the hands of the soldiers sent by Marco Antonio, who claimed his head as a trophy to expose it in the forum.

The five great jurists of Roman Law | Law history

The jurists before the courts, could cite the works of the masters Papinian, Gaius, Ulpian, Paulus and Modestinus, as a reference of authority.

If the opinions of these jurists did not coincide, the judge should decide to favor Papinian’s opinion.

According to the Dating Law promulgated by Emperor Theodosius I, in 426 AD. of C., the opinions, opinions or judgments of the jurisconsult influenced on the Roman law.

For this reason, they were collected by the Emperor Justinian, in his Corpus Juris Civilis, and, later, by the great medieval jurists.

1. Ulpian (170? – 228) a. of C.)

Ulpian (in Latin: Gnaeus Domitius Annius Ulpianus) is considered one of the greatest jurists in the history of Roman Law.

His most important work was the compilation and ordering of classical law, where he highlighted his comments “Ad Edictum” and “Ad Sabinum”.

“Justice is the constant and perpetual will to give each one his own right”

Likewise, he wrote various texts on the powers of magistrates and imperial officials and the writing of the Digest of Justinian is based on the fragments of him.

Ulpian pronounced famous phrases such as “Durum est, sed ita lex scripta set” (it is harsh, but that is how the law was written, a principle that he defended when he was expelled from Rome in 200 BC by the emperor Heliogabalus. He also recited his expression “Res iudicata pro veritate accipitur” (The thing judged is considered certain), among many.

Ulpian’s rules

The Ulpian rules consisted of three basic principles: live honestly, do not harm others, and give each one his own.

Ulpian, was part of the imperial bureaucracy as an advisor to Emperor Alexander Severus. He served as prefect of the praetorium, but the praetorian soldiers did not agree with a jurist leading them and limiting their economic benefits, so they rebelled against him. Finally, he was beheaded in the presence of the emperor.

The definition of Justice and the legal precepts of Ulpian are still in force today in all areas of law. However, the problem with his approach, “give each one his own”, lies in finding out what corresponds to each one; for which there has been a great discrepancy throughout history.

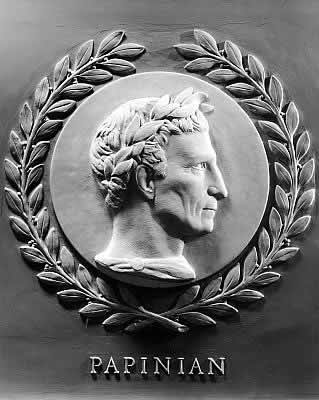

2. Aemilius Papinianus (142 – 212 BC)

His statue is located in the Plaza de la Villa in Paris, at the headquarters of the Supreme Court of Spain.

Papinian or Papiniaus lived between the 2nd and 3rd century AD. of C, and was the number one of the great jurists of ancient Rome.

His most important works were the Quaestiones, made up of 37 books, written before 198 AD. of C., and the Responsa, elaborated between the year 204 and the date of his death in 212 d. by C.

He also wrote two works, adulteriis, two books of Definitions and a text in Greek in which he established the duties of the magistrates and urban police officers of the time.

As a jurist, Papinian always stood out for his independence of opinion and his desire to find equitable solutions, which led to his death.

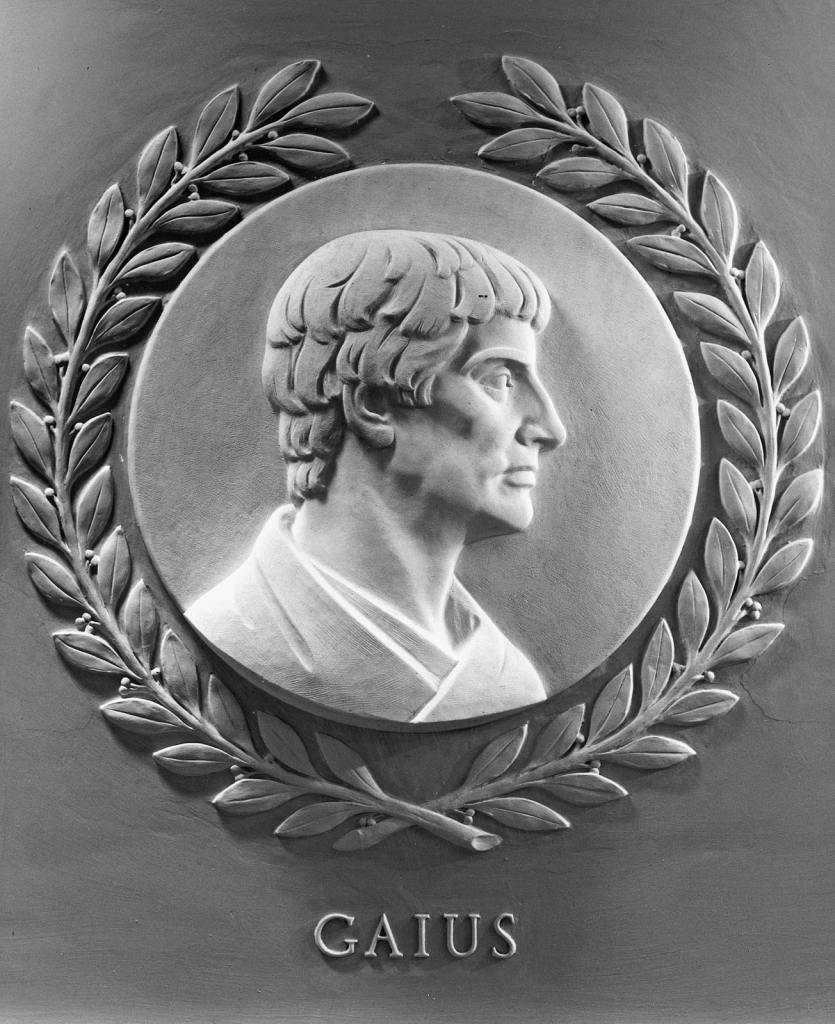

3. Gaius (130 – 180 BC)

Gaius is one of the most enigmatic jurists. He dedicated a large part of his life to teaching law and almost all of his work had an educational purpose such as the Institute, a law manual dedicated to teaching.

Most of his works were written during the government of the emperor Antonio Pío and, at the beginning of the mandate of the emperor Marco Aurelio.

Unlike the jurisconsults of his time, Gaius did not hold public office, nor did he enjoy the ius publice responndi, which was the authorization granted to jurists to give legal opinions on behalf of the emperor. Despite this, his Intitutas were disseminated during the Roman Empire and used until the time of Justinian.

The palimpsest manuscripts was one of Gaius’s most famous works, discovered by the German historian Berthold Niebhur in the Cathedral of Verona in 1816.

The Institute of Gaius is included in the content of the Digest, the Institutions of Justinian, and some other quotation.

From the analysis of the texts of Gaius, some jurists maintain that he was not very aware of the doctrinal evolution of the time and he was considered as a simple author of legal manuals.

4. Julius Paulus Prudentissimus

Julius Paulus Prudentissimus was one of the most influential Roman jurists who provided legal advice to the Praetorians and served on the imperial council during the reigns of Septimius Severus and Caracalla.

Julius Paulus was exiled by Heliogabalus and returned to Rome in the mandate of Alexander Severus, who appointed him prefect of the praetorium.

Among his writings stood out the 78 books ad Edictum, which tried to follow the edict legislation and two books in which he analyzed the edilicio edicts.

Paulus wrote several works by previous jurists, among which were Juliano’s digesta, Papinian’s responsa and quaestiones.

He was the author of two books on institutes and six on regulae, commentaries on various laws and senateconsults, referring to the duties of imperial officials and on matters of fiscal and criminal law. Furthermore, he commented on the leges of Augustus: Iulia et Papia Poppea and Iulia de adulteriis.

He also wrote the libri responsorum in responses to concrete practical cases, arranged according to the edict system; as well as, the 25 books of quaestiones and the 23 of responsa of a causal nature.

In the Vatican Library there is a document that contains fragments of comments on the imperial legislation attributed to Paulo.

5. Herenius Modestinus (170 – 228 AD)

He was the last of the classical jurists of Roman Law. He was a disciple of Ulpian and wrote elementary works for teaching, some Institutions of ten books.

The main ones were the Pandects in 12 books and the answers in 19, received in 344 fragments in the Justinian Pandects.

The excuses, by Modestinus, is the only classical monograph written in the Greek language, linked to the interests of the Greeks in the eastern provinces. The lawyer also compiled the legal transformations derived from the constitutio; as well as, the existence of Roman law treaties in the Greek language is owed to him. From his work De excusationibus, written in Greek, an important part of fragments is preserved in the Digest.

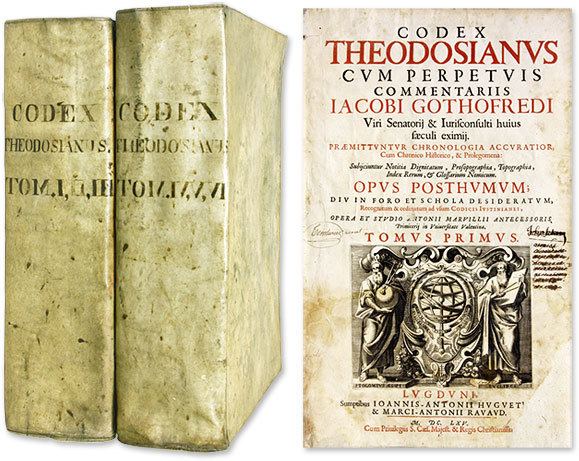

The Theodosian Code (503 AD) | Law history

The Theodosian Code is a compilation of the laws in force, whose drafting began by order of the Emperor Theodosius II, in the year 429 d. It was promulgated in the eastern part of the empire in 438 AD. of C. by the mentioned monarch, and a year later it was legalized in the West by order of the emperor Valentinian III.

Its structure consists of 16 books divided into titles such as the Imperial Constitutions arranged in chronological order. The first five books refer to private law; the sixth, seventh and eighth, deal with administrative law; the ninth refers to criminal law; the tenth and eleventh, to tax law; from the twelfth to the fifteenth, they refer to communal law; and the sixteenth relating to canon law.

The Theodosian Code was written in Latin, being the official language of the Empire. In its content, public law predominates over private law and there are rules aimed at imposing religious orthodoxy against heresies.

Among its laws, the code contains 65 decrees directed against heretics, as well as a compendium of provisions to regulate the segregation of Jews.

The Code was in force, particularly, in the Eastern Empire until the regime of Justinian I, when Roman Law was reorganized in the Corpus Juris Civilis promulgated by the emperor.

Likewise, the Code was published on February 15, 438 BC. of C. and entered into force on January 1 of the following year.

Finally, the Codex Vetus repealed the Theodosian Code on April 17, 529; however, in Western Europe it remained in force longer; constituting the basis of the Roman laws of the Germanic kingdoms.